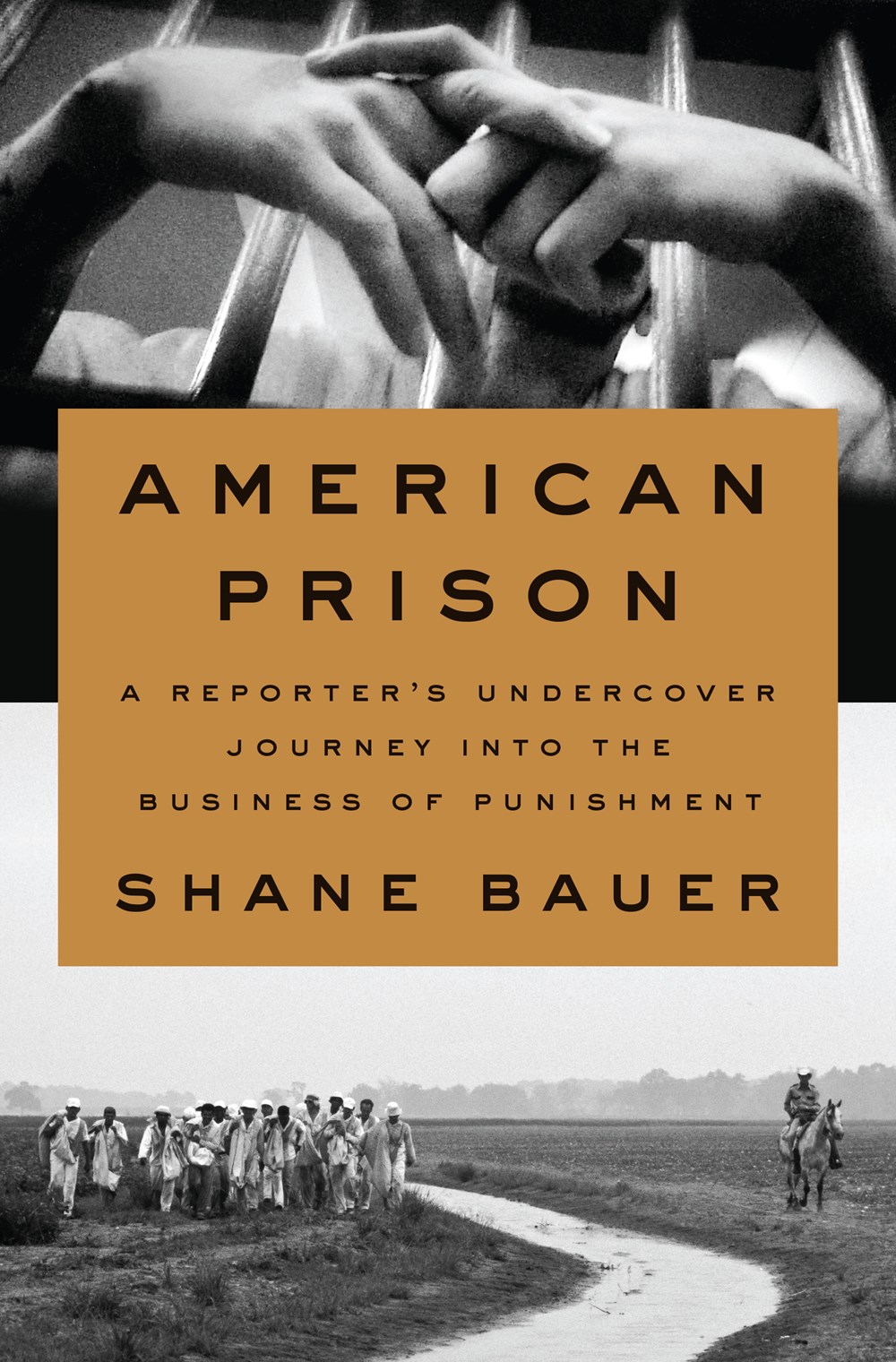

American Prison: A Reporter's Undercover Journey Into the Business of Punishment

October 03, 2018

Our owner and CEO takes a look inside the country's prison industrial complex, and its long history, through the lens of journalist Shane Bauer's new book.

The day President Trump was elected, the stock of CoreCivic rocketed 50 percent, increasing in value more than any other company on the US stock market. A year and a half later, as recorded in The New York Times, CoreCivic’s CEO crowed about his business’s forecast, heralding the climate as “the most robust kind of sales environment we’ve seen in years.” CoreCivic is one of America’s two largest private prison corporations, and it seemed it was about to see its considerable lobbying efforts and ample contribution to the Trump inauguration committee well rewarded.

Shane Bauer’s new book American Prison is a cogent and absorbing examination of how we got to this place, how profiting off the incarceration of others is in fact fundamental to our American experience, and how in private prisons, race, and money are inextricably linked. A journalist for Mother Jones magazine, Bauer himself spent over two years in an Iranian jail—four months in solitary confinement—after accidentally hiking across that country’s border with friends. Out of confinement for just three years, Bauer was nevertheless drawn to prisons as familiar mooring to process his own experience and its emotional fallout. Beyond his personal connection, he saw the significance of the growing industry. As he says, “We now have almost 5 percent of the world’s population and nearly a quarter of its prisoners. When we look back in a century, I am convinced that our prison system will be one of the main factors that define the current era.” Though undercover journalism, long an important element in exposing American governmental and corporate abuses, has lately run up against litigious roadblocks, Bauer and his editors determined that it was the only way to truly see into this secretive and powerful world of private prisons. Intercutting the story of his time as a corrections officer (a CO) at Louisiana's Winn Correctional Center with a comprehensive history of incarceration in America, Bauer crafts an engrossing and disturbing story of white America’s impulse to use convenient justification and cunning maneuvers to secure power and profit through imprisoning a largely black population.

The book’s delineation of the immeasurably corrupt past and present of incarceration in this country uncovers a history and legacy I knew little about. The following is a small sample of the many, many interesting—and often deeply concerning—developments in our nation’s historical approach to criminal justice that Bauer examines with compelling detail.

American Prison catalogues how the history of our government and our fellow citizens benefiting financially on the backs of the powerless finds its origin in pre-colonial days when British convicts were sent here to be used by tobacco planters, who took advantage of both their labor and their temporary status. As Bauer points out, slaves were expensive and required a certain ongoing investment, but workers who belonged to another entity were cheap and expendable.

American Prison reveals that after the American revolution, it was the Protestant governing establishment that popularized the notion that hard work and discipline were wanting in the criminal class, which precipitated more permanent “penitentiaries” and replaced jails that had held people only until sentenced. The cessation of slavery in the North in the early nineteenth century bolstered the value of these penitentiaries; they were just the place to contain freed former slaves deemed threatening to white rule. Separating the inmates, enforcing a strict code of silence and punishment, turning them into “insulated working machines”—this was slavery by another name. (Indeed, a PBS documentary about inmate leasing was called just that: Slavery by Another Name.) And when both states and contractors determined that considerable monies could be made leasing inmate labor, this approach—using people who had little perceived social value and were easily replaceable to benefit those who controlled them—became the backbone of our penal system for nearly a century.

American Prison illustrates how, with the advent of the steam engine in the South, cotton production revved up (as well as the production of goods that used it, like cotton bagging and rope) such that there simply were not enough inmates to do all the work. For the South to really compete industrially with the North, the equation was simple: more output required more input. From trumping up charges to arrest more people, to selling inmates’ children to prison labor lessees, more expendable workers were amassed and profited from. “Five years after Texas opened its first penitentiary,” Bauer writes, “it was the state’s largest factory. It quickly became the main Southern supplier of textiles west of the Mississippi.”

American Prison explores how the collapse of the South following the Civil War gave rise to two immediate necessities, one sinister and one structural—both of which found an answer in convict leasing: how to continue the subjugation of four million freed slaves and reinforce white supremacy, and how to rebuild. Prior to the war, Bauer tells us, seven of the eight wealthiest states were south of the Mason-Dixon line and the majority of Southern convicts were white (of course: most Southern black people were slaves). Following the defeat of Dixie, however, seventy percent of prisoners were now black. Through a loophole in the Thirteenth Amendment that made slavery and involuntary servitude unlawful “except as punishment for a crime” [emphasis added], so long as black men could be said to be breaching the law, they could be leased by the states to serve their time laboring at private cotton and sugar plantations, as well as lumber, coal, and railroad companies to be used, abused, and tossed away. The conditions under which convict miners, for example, worked and lived—forced to drink water from a river that was used upstream as their toilet, being housed adjacent to the coke ovens bilging gas, carbon, and soot—were only surpassed in horror by the experiences of the convicts leased to build the railroads. The widely accepted racist notion that black people could absorb more pain and suffering than their white counterparts was used to justify the abuse—as did the money being made off their labor. Indeed, the two states running the most merciless convict leasing systems in the late nineteenth century, Alabama and Tennessee, made the most money.

American Prison makes manifest that when the practice of convict leasing was finally phased out, it was surely not for humanitarian reasons. Rather, because the competition for the captive labor force had so increased with many more eager companies bidding on leasing contracts, the wages companies were forced to pay came closer to those paid to free laborers. Offering higher pay meant fewer profits, the central benefit of convict labor to a private company. Ultimately, revelations about the manipulative and, in fact, illegal methods by which people were transformed from poor and usually black to "criminal," and the brutal beating and murder of a young white convict signaled the death knell of convict leasing in America. This practice didn’t end, however, until more leased prisoners died over the course of its practice than in the gulags of the Soviet Union.

Bauer brings us to the present day by interspersing accounts of his time between January and May of 2015 as a CO at the Winn Correctional Center, located about 3 hours north of Baton Rouge in the middle of a national forest. These chapters tell the often harrowing story of life inside Winn and, in concert with his historical study, flesh out the brutality and venality of the private prison system in this country. From the paltry hourly wage of $9 an hour (even the inmates think the guards should be paid more, one saying to a CO, “They do need to give y’all a pay raise”); to the deliberate refusal to staff the prison adequately to secure the safety of either the employees or the inmates (staff had been slashed to two guards per 350 prisoners); to the cutting of any real and consistent programming for prisoners at Winn despite the institution’s contract with the state requiring the inmates to be assigned to “productive, full-time activity” five days a week—through example after example, Bauer reveals Winn to be a slipshod, bare-bones human warehouse. In the same way in which the (mostly black) leased convicts had been seen as expendable labor in the previous era, so now the population of Winn (75% black when Bauer worked there) was also treated as disposable. In one of Bauer’s first days of training, the instructor tells his trainees that if they see two inmates stabbing each other, other than “holler stop,” there’s nothing more they can do. He takes up the refrain: “We are not going to pay you that much” to try to break up a fight. Bauer wonders, “How do you justify paying fast food wages to people who risk their lives on a daily basis?”

He makes mundanely clear how today’s private prisons profit on their prisoners: Not only did a Department of Corrections investigation discover that inmates had been charged for using toilet paper and toothpaste supplied by and paid for by the state, but prison companies have written “occupancy guarantees” into their contracts, requiring states to pay a fee if they cannot provide a certain number of inmates. Winn Correctional Center was guaranteed to be 96 percent full. The similarity to the convict leasing of the past lay in the state and federal governments again awarding contracts to private corporations, but this time rather than working the inmates, they were paid by the number of inmates they housed. (This was a system ideal for profiteering off a national prison population that almost doubled between 1976 and 1986, and then exploded to 1.6 million by 2009). While Bauer was at Winn, that meant a guarantee of $34 a day for at least 1,440 prisoners, or $48,960 in revenue a day. The less spent on guards, food, classes, mattresses, healthcare, working toilets, the more profit. Keeping overhead low was a critical business strategy.

One of American Prison’s great strengths is the extent to which Bauer explores his own deep ambivalence about working at Winn, first about what his attitude toward the inmates should be given his own experience as a prisoner and the false pretenses under which he’s there, then about his secret satisfaction at his commands being heeded, and later about his being complimented by a superior as an “outstanding officer” with a “take charge attitude.” Bauer’s candid self-reflection makes him an earnest and insightful guide to the unnerving combination of violence and neglect that characterizes relationships at Winn, and to the strange but logical symbiosis between the COs and the inmates. As one prisoner says to a guard, “It’s your home for 12 hours a day! You ‘bout to do half my time with me.” Early in the book, Bauer’s citing of the Stanford Prison experiment—that infamous trial revealing people’s tendency to become their assigned roles, whether victim or victimizer—comes to feel prescient: “Who am I becoming?” he wonders, just before he determines that he must leave Winn. “Inside me there's a prison guard and a former prisoner and they are fighting with each other, and I want them to stop.”

While Bauer was there, Winn was owned by the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), a company that managed more than 80 state and federal prisons and detention centers across the country. Many of its facilities rife with instances of filthy conditions, inmate neglect, and wrongful deaths, CCA nevertheless is repeatedly accredited by a national trade group, American Correctional Association, a seal that then inoculates the company from accusations of laxity or cruelty. (In an exquisite bit of fox-guarding-the-henhouse finesse, the head of CCA had also been the head of the accrediting agency.) And how does CoreCivic, the company that welcomed the present “robust sales environment” fit into the equation? CoreCivic is the rebranded name of CCA, that expert in, as Bauer says, “cashing in on captive human beings.”

As for this historical moment, it would be an understatement to say that these are good times for private prisons; between many states’ use of truth-in-sentencing laws and breakneck immigration detention (and the splitting up of those families requiring separate housing facilities), the private prison industry is booming. Just in time, Shane Bauer’s examination of the “business of punishment” is both wide-ranging and intimate, an essential exposé of one of the most mercenary of American enterprises.