Inside the Longlist: Narrative & Biography 2018

December 19, 2018

Company owner and CEO Rebecca Schwartz looks inside the covers of the top five Narrative & Biography books of 2018.

What is laid down, ordered, factual is never enough to embrace the whole truth: life always spills over the rim of every cup. ~Boris Pasternak

While at some points in our lives books chock full of facts and statistics are helpful to understanding a specific problem or landscape, these (supposedly) unbiased truths are seldom enough to grasp the full scope of the subject at hand. For that, these facts and stats need to be wedded to the people impacted by them, need to be interpreted for the way they influence and shape real life. All five books on this year’s Narrative and Biography shortlist do exactly that: they feature families and children and old women and workers and convicts and dreamers who show the humanity of the numbers, the heartbreak and the triumph of what is only partially captured by plain facts and figures (though all the authors include plenty of these too). Indeed, it is the personal stories that actually give weight to the numbers, the contextualization that make the sums and scores impact us as they do. Without the stories of the people destabilized by the cultural transformation of work, the families caught in the booms (and busts) of the Texas oil fields, the devastation of individuals wrought by short-sighted and rapacious Big Pharma, the lived experience of prison workers and inmates, the dismissed but proud and persistent people of the Kansas plains—well, all the data in the world couldn’t make us feel the way we do reading these folks’ stories.

Temp: How American Work, American Business, and the American Dream became Temporary by Louis Hyman, Viking

Temp: How American Work, American Business, and the American Dream became Temporary by Louis Hyman, Viking

In this deeply researched and timely examination of the transformation of work in America, Louis Hyman demonstrates through a sweeping historical survey that the rise of the temporary or “gig” economy was not due simply to the increasing power of Silicon Valley or a random convergence of events. Rather, it was by deliberately privileging the market and its experts (especially consultants) and strategically rethinking the corporation as strictly a vehicle to make money that post-war assurances of workers’ security and protection were abandoned for the shareholder values of risk and flexibility. Through example after example, Temp shows us the results of this new catechism in the form of consolidation, cost-cutting, and wealth concentration. From Milwaukee’s own Elmer Winter, the president of the temporary labor firm Manpower who in the 1960s championed “dynamic management” in order to maximize profits, through Galbraith, Drucker, McKinsey, and Warren Bennis, Hyman takes us up the ladder of corporate transformation and down the ladder of labor instability. In the process, he reveals the way that this new workplace volatility was actually the same old, same old for women and people of color, who’d never experienced anything but, and that what was so rattling about the cultural shift was that white, male workers came acutely to feel its impact. Interestingly, Hyman also offers a fresh argument for the ways in which work untethered to a punchclock and a boss could be the basis of a more inclusive, egalitarian, and fulfilling future for all. Reading this thoughtful exploration of work in America is to understand what led to our current moment and to envision possibilities for making both work and the life it supports more meaningful.

The Kings of Big Spring: God, Oil, and One Family’s Search for the American Dream by Bryan Mealer, Flatiron Books

The Kings of Big Spring: God, Oil, and One Family’s Search for the American Dream by Bryan Mealer, Flatiron Books

In what is one of my favorite books of this year, Bryan Mealer tells the sprawling, compulsively readable story of his family’s departure in the late nineteenth century from a Georgia hollow to land in Big Springs, Texas, where they endured and enjoyed more than a hundred years of hard luck and hard-won victories. The Kings of Big Spring is the quintessence of an American story: a family goes west in search of a better life and encounters enough adventure and pain to keep five generations wondering why they settled there in the first place. From boll weevils to droughts, sandstorms to booms and busts across the oil rich Permian Field of Texas, the fear of God’s wrath and longing for God’s mercy, Mealer’s book is part family biography and part elegy to a flawed and beautiful people. As is fitting for the Lone Star state, The Kings of Big Spring is populated by larger-than-life folks experiencing larger-than-life events, all seemingly to the distant soundtrack of a soulful and lonesome Johnny Cash tune. Nobody takes up as much emotional space as Grady Cunningham, a sometimes friend of Mealer’s father, who in the last section of the book comes into his full glory as a man bent on becoming a millionaire and offering a portrait of someone as self-destructive as he is self-made, fueled by oil, cocaine, and the goodwill of others. Mealer has said his story is a mash-up of The Grapes of Wrath and “Boogie Nights,” and while this description works as shorthand, to immerse oneself in this magnificent and nuanced history of a family and the land it lived on is to take a trip through a part of American history and geography that will stay with you for a long, long time.

Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and The Drug Company that Addicted America by Beth Macy, Little, Brown and Company

Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and The Drug Company that Addicted America by Beth Macy, Little, Brown and Company

The latest, December 2018 full-page advertisement in the New York Times by Purdue Pharma, makers of OxyContin, did little to salve the pain that very company has brought to millions of families and exactly nothing to bring back these families’ loved ones who died as a result of their addiction to Purdue’s pills. In a gripping, disturbing and indispensable study, Beth Macy’s Dopesick puts very human faces on today’s opioid epidemic by tracing its origins and illustrating its impact on those left in its wake. From morphine to heroin to OxyContin and back again to heroin, Macy reveals the convergence of a number of factors that got us to our current crisis: doctors’ widespread use of the pain scale and its implied expectation of zero pain as the singular goal, the release of OxyContin in 1996 and the absence of its regulation; the advent of doctors wanting to please patients who would otherwise review them harshly and publicly; those same doctors being flooded with incentives and sales reps hawking Oxy who rewarded heavy prescription-writers for everything from cancer to a child’s sprained ankle; the hollowing out of communities left behind by companies moving manufacturing offshore; the failed War on Drugs’ incarceration of users far more often than dealers; the myriad barriers to treatment; the rise of a generation of children accustomed to taking pills for ADHD for whom the notion of pill taking was second nature—all these developments and more clustered in a crucible of cataclysmal addiction, first to Oxy and then to its cheaper, more readily available cousin, heroin. Focusing on a few counties in southwestern Virginia, Macy’s Dopesick is simply essential reading to understand on an intimate scale the results of deeply flawed drug policies, corporate greed, and human desperation. Through this book, we come to see that it’s not just the addicted who are dopesick, but the country that allows them to become so.

American Prison: A Reporter’s Undercover Journey into the Business of Punishment by Shane Bauer, Penguin Press

American Prison: A Reporter’s Undercover Journey into the Business of Punishment by Shane Bauer, Penguin Press

A cogent and absorbing examination of how America came to have just five percent of the world’s population and nearly 25% of its prisoners, Shane Bauer’s American Prison takes us through the history of private prisons from the time of our country’s founding through the present, revealing the engrossing and disturbing story of how profiting off the incarceration of others is in fact fundamental to our American experience, and showing how in private prisons, race, and money are inextricably linked. Perhaps most notably, Bauer’s account makes clear that the widespread system of convict leasing was developed in the South as a response to the newly freed slaves being perceived as a threat to white employment—and white supremacy. For nearly a century, state and local governments contracted for-profit private companies to house, and lease out the work of, their inmates. This was, in fact, slavery by another name. Intercutting the history is Bauer’s account of his time as a corrections officer at Louisiana's private Winn Correctional Center, which offers personal insight into the venality and corruption he describes on a national scale. Both staff and inmates there are locked in a mutually dependent misery of institutional corner-cutting, chronic abuse, and enervating apathy; Bauer makes it clear that Winn is emblematic of the brutality and ugliness of America’s larger private prison system. In American Prison, his examination of the “business of punishment” is both wide-ranging and intimate, a timely exposé of one of the most mercenary of American enterprises.

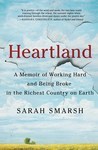

Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth by Sarah Smarsh, Scribner

Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth by Sarah Smarsh, Scribner

In a time when divisions between “us” and “them”—whoever we and they are—seem nearly unbridgeable, Sarah Smarsh’s memoir Heartland offers welcome insight into an often stereotyped, derogated population: the working poor in what is known dismissively as “flyover country,” the towns and family farms of Kansas, Smarsh’s heritage. Through deft storytelling and the deliberate connections between her family’s economic circumstances and the country’s national fiscal and social policies, Smarsh offers a soulful and searing condemnation of the nearly insurmountable class divide that renders the American Dream a false promise for so many. Sometimes it is, as Bob Dylan sang, a simple twist of fate that spins our lives in one direction or another, while in other cases it is teeth-gritted determination that forges the people we become. For Smarsh, avoiding the fate of single motherhood, as so many who came before her could not, was the result of sheer will, a mission to do something “big” that could only happen if she broke the “maternal cycle” she was born into and thus the poverty that entrapped many of the women in her fifth-generation Kansas family. Through Heartland, we see the burden of frequent moves (how can a child keep up with math when she moves 48 times before she’s 15?), the eagerness to form connection (though marriages born of this haste are often disappointing and short lived), and the toll of low wages, and unstable and unsafe working conditions (Smarsh’s father was poisoned by toxins and nearly incapacitated while in the employ of a chemical company). An affectingly personal, poetic memoir, Heartland reveals a woman—and a people—as resilient and hardworking as any, “us” or “them.”