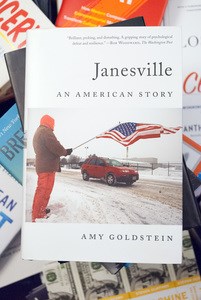

In Praise of Janesville: The 2017 800-CEO-READ Business Book of the Year

January 18, 2018

Eminently accessible, instantly absorbable, Janesville is a story of economics lived. Of the decisions a monolithic company makes that results in economic devastation for a middle-American town, and the families that live there. A microcosmic illustration of a national experience, Janesville is about idealism and stubbornness and desperation and bravery. And we all can learn a lot about ourselves and our capacity for resilience from the children whose stories are at the heart of Janesville.

“Even a small city wrenched by the worst of what a mighty recession metes out does not have a single fate. With broad outside forces—the federal government and the state, industry and labor—unable to lift back up its once prosperous middle class, Janesville has been left to rely to a considerable extent on its own resources. Fortunately, those resources include more generosity and ingenuity—and less bitterness—than in many communities that have been economically injured. Still, over time, some people prosper. Some grieve. Some get by.”

Amy Goldstein, Janesville

Janesville, our 2017 Best Business Book of the Year, is a microcosmic illustration of a national experience. It is the story of a city and its peoples’ resilience and adaptability after the local GM plant—the gold standard of employment for generations—was closed. Impersonal business decisions inflict intimately felt pain as change becomes a necessity, not a choice. The book is about idealism and stubbornness and desperation and bravery, masterfully told by Amy Goldstein in interwoven, multi-dimensional story strands. Goldstein handles adeptly a large cast of characters, from politicians and the economically affluent who guide the city’s tenuous recovery, to the men and women who are left only to react to the decisions made by them, and who are forced to make their own decisions, good and bad, revealing the effects the fallout of the plant closure wreaks upon the upcoming generation.

Janesville, our 2017 Best Business Book of the Year, is a microcosmic illustration of a national experience. It is the story of a city and its peoples’ resilience and adaptability after the local GM plant—the gold standard of employment for generations—was closed. Impersonal business decisions inflict intimately felt pain as change becomes a necessity, not a choice. The book is about idealism and stubbornness and desperation and bravery, masterfully told by Amy Goldstein in interwoven, multi-dimensional story strands. Goldstein handles adeptly a large cast of characters, from politicians and the economically affluent who guide the city’s tenuous recovery, to the men and women who are left only to react to the decisions made by them, and who are forced to make their own decisions, good and bad, revealing the effects the fallout of the plant closure wreaks upon the upcoming generation.

And it is the next generation, the children of Janesville, who show us through their stories our nearly infinite capacity for resilience. It is the children who became the most unwitting casualties of impersonal business decisions and the trickle-down impact those decisions had on the topography of their lives. And it is the children who I cannot forget long after reading the book and who I think of as I recommend the book to new readers.

There is Chelsea, the daughter of a Janesville bank president, who takes charge of the city’s economic development:

Mary Willmer has not forgotten the October night she came home to find Chelsea, her fifteen-year-old, crying in a circle with friends whose parents were losing their jobs, asking her what she intended to do about the situation. The answer begins to reveal itself in January. Just after the plant has closed, a tiny team starts to convene in secret once a week.

Bria, the daughter of a GM “gypsy” who elects to take a transfer to another GM plant which requires him to drive long distances and be away from home for weeks at a time. He has a guaranteed job, but what of the sacrifices?

Bria can tell that dad says to her and Brooke all the things he thinks will make them feel as good as they can about him being away: If he were still working second shift at home, it’s not as if he would be around anyway when they get home from school or for dinner. And if he hadn’t taken the GM transfer, who knows how much time he really would have had with them, if he’d ended up with a a job in town that didn’t pay enough so he had to take a second job on weekends, like some kids’ parents are doing. Even as a fourteen-year-old freshman, Bria knows that what they need to do is just do the best they can. And that’s what they do.

Alyssa and Kayzia, daughters of a laid-off factory worker who, at first, is actually relieved to no longer have to work at the plant. The opportunity for a change is welcome, but several years of job hopping and penny-counting has made him depressed as the girls grow into adults, supporting at many turns their own parents.

In the past three years, she and Alyssa have become experts at hiding what is going on at home. They have become skillful at poking through the clothes at Goodwill to find designer jeans that look as if they got them new. And going along when their friends want to go shopping without drawing attention to the fact that they aren’t buying anything. What’s going on at home is not something to discuss with their friends.

[...]

Hard as it is to imagine, in Janesville where thousands of people have lost jobs and some are still out of work and some, like her dad, are job hopping and not earning enough money, it has never occurred to Kayzia before that what is going on in her family is going on all over town.

The city itself mirrors what each child learns to enact daily: putting on a brave face and learning to live with less.

Without its assembly plant, Janesville goes on, its surface looking uncannily intact for a place that has been through an economic earthquake. Keeping up appearances, trying to hide the ways that pain is seeping in, is one thing that happens when good jobs go away and middle-class people tumble out of the middle class.

Perhaps their stories resonated so strongly with me because I was 14 years old in 1985 when the union of my hometown’s local Hormel meat-packing plant went on strike in response to a lowering of the hourly wage. Austin, Minnesota still calls itself “The Hometown of Spam,” so you can imagine the impact on the community. My memory of those six months are vague at best—in part because I was raised on a farm miles outside of Austin and I went to school in a small town even further away. But my father worked in Austin, and my uncle owned a small motor and mechanic shop in town, so while the impact was indirect, my attention was captured. During the nightly news, I remember hearing about anger, about “The Union,” and most notably, I remember hearing the word “scab,” often. I remember understanding that people were taking sides. I remember thinking there were villains.

Thinking back, the strike created an uncertainty in the community that was pervasive, slyly reaching its tentacles in all directions, with no center, no right, no wrong. It ignited questions in me. What was a job, and who might be willing to step away from theirs? What was a job, and who might be willing to take someone else’s because, well, a job was a job? How did any man or woman who was a husband or father or wife or mother commit to a mission greater than themselves that might hobble their family’s financial prospects for years? How did any family afford for their main earner to not earn?

The intricacies of Austin’s economic health didn’t directly affect me or my immediate family in a way that I was aware at 14. Still, I believe witnessing the Hormel strike taught me a level of empathy that I carry with me today. For people who have never experienced an abrupt economic downturn, a book like the excellent and justifiably celebrated Janesville offers a similar, and most critical, lesson in empathy. Amy Goldstein allows us to bear witness to the pain, the hope, and the effortful recovery that is required when business decisions inflict very human consequences.