The Big Nine: How the Tech Titans and Their Thinking Machines Could Warp Humanity

March 29, 2019

Amy Webb's book is a look at where AI comes from and where it is going, laying out three scenarios—from "optimistic to pragmatic to catastrophic"—of where it could lead us in the next 50 years.

The Big Nine: How the Tech Titans and Their Thinking Machines Could Warp Humanity by Amy Webb, PublicAffairs, 336 pages, Hardcover, March 2019, ISBN 9781541773752

Amy Webb’s new book, The Big Nine, is a feat of intellect, erudition, and imagination. It is the futurist’s examination of where AI is heading and its potential effects on humanity, but it is also an exploration of our humanity, and a history of intelligence—artificial and otherwise.

Webb traces the history of AI a bit further back than you might imagine—not to early technologies like the calculator, or the even earlier automatons of the sixteenth century, but to the syllogistic logic of Aristotle and invention of the algorithm by Euclid:

Their work was the beginning of two important ideas: that certain physical systems can operate as a set of logical rules and that human thinking itself might be a symbolic system.

It is in this way of considering intelligence generally, in bringing the mathematical, scientific, and philosophical traditions of the western world to bear through the theories of Hobbes, Descartes, Leibniz, Hume and so many others that Webb brings us to Ada Lovelace and Charles Babbage, and the invention of the first computer program in the 1820s. It is an intersection of disciplines that the first machines we would recognize as a modern computer also relied on, as Boolean logic and algebra (from George Boole) would prove just as important as it would electrical circuits. Webb explains how it was “an unusual diversion” from his electrical engineering courses at MIT that led Claude Shannon to an elective philosophy class, where he discovered Boole’s An Investigation of the Laws of Thought, which he used in his seminal paper “A Symbolic Analysis of Switching and Relay Circuits” in the 1930s. So it is, in the beginning, as much about the nature of thought, how we think about how we think, as it is about how we’ve taught machines to “learn” and “think.”

The question of whether machines can think, or can be creative, is in some ways moot. Machines are already thinking, and creating real-world outcomes. It is beginning to touch everything in our lives, from the intensely personal to the panoramic, things like “the global economy, the workforce, agriculture, transportation, banking, environmental monitoring, education, the military, and national security.” All of which makes the fact that the creators of AI come from such a homogenous group is troubling. As Webb writes:

I believe these people are well intentioned. But as with all insulated that work closely together, their unconscious biases and myopia tend to become new systems of belief and accepted behaviors over time. […] And that thinking is what’s being programmed into our machines.

That any community can be insular is not surprising, but the one that builds systems intended to make decisions on all our behalf should not be. We should also insist AI not perpetuate stereotypes, prejudice, or injustice, yet it may—as “one of the neural nets at universities,” Word2vec, created by Google for university students to learn on has—do just that:

For example, it learned that “man is to king as woman is to queen.” But the database also decided that “father is to doctor as mother is to nurse” and “man is to programmer as woman is to homemaker.”

One could argue that even “man is to king as woman is to queen” is discriminatory against same-sex couples. Webb also reminds us of Microsoft’s AI twitter bot experiment, which became virulently racist and antisemitic in just 45 minutes online. But the problem isn’t limited to that aspect of AI learning prejudice. The AI used in hiring at the Big Nine also discriminates against candidates with coursework in areas outside of AI—coursework in fields like the humanities and literature, and even theoretical physics and behavioral economics— would expand and diversify the experience and worldview of the people working on AI. This and more means that “entire populations are being left out of the development track.”

That is a problem because we have not only created artificial intelligence that make decisions we cannot predict, we have created artificial intelligence that makes decisions in ways we don’t entirely understand, and cannot replicate, and it has embedded in it the values and biases of a very insular tribe. Not only that, Alphabet’s Google Brain division has created an AI that is now “capable of generating its own AI” that outperforms human coders. I don’t even know how to wrap my head around that worm home of nested Russian dolls, or its possible implications. But Amy Webb might, and she doesn’t mix metaphors or mince words. She is unequivocal in her belief that, yes, machines can think. Not only that, but that they are capable of original thought. In fact:

Thinking machines can make decisions and choices that affect real-world outcomes, and to do this they need a purpose and a goal. Eventually they develop a sense of judgment. These are the qualities that, according to both philosophers and theologians, make up the soul. Each soul is a manifestation of God’s vision and intent; it was made and bestowed by a singular creator. Thinking machines have creators, too—they are the new gods of AI, and they are mostly male, predominantly live in America, Western Europe, and China, and are tied, in some way, to the Big Nine.

That is not because women and other underrepresented groups are not capable of doing this work, or that it is not necessary. It is necessary, if we want AI to be more empathic, inclusive, and less biased. And, as we know from many books we’ve reviewed here—like Brotopia and Broad Band—computer programming, from Ada Lovelace down to the moon landing, was once dominated by female workers.

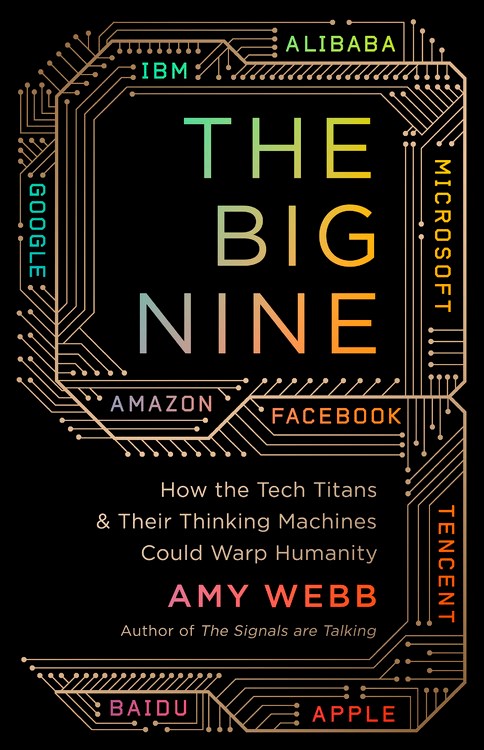

But The Big Nine isn’t just a story about the bias embedded in tech. It is also a geopolitical tale. The “Big Nine” refers to the nine tech companies shaping the present and future of AI today:

Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook, IBM, and Apple in America, and Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent in China. The difference between the two country’s approaches is wildly different, one dominated by markets, and the other by the state, which is so devoted to AI as a national strategic objective that “Chinese kids begin learning AI skills in elementary school.”

This is China’s space race, and we are its Sputnik to their Apollo mission. We may have gotten to orbit first, but China has put its sovereign wealth fund, education system, citizens, and national pride on the line in pursuit of AI.

The three Chinese members of the Big Nine already have staggering numbers. Tencent’s WeChat has 1 billion monthly active users, and overtook Facebook last year as the world’s most valuable social media company. It is also used in more ways than Facebook, for everything from text messaging and making payments to patient management and law enforcement. And WeChat is but one of the company’s services, a diversity which helps explain how “less than 20% of Tencent’s revenue comes from online advertising, compared to Facebook’s 98%.”

Baidu had 665 million mobile search users in 2017—more than double the estimated number of mobile users in the United States.

And while “Amazon had its best-ever holiday shopping season” in 2017, selling raking in $6.59 billion on orders of 140 million products between Thanksgiving and Cyber Monday:

Alibaba sold to 515 million customers in 2017 alone, and that year its Singles’ Day Festival—a sort of Black Friday meets the Academy Awards in China—saw $25 billion in online purchases from 812 million orders on a single day.

She envisions a scenario in which China easily gains a military and economic advantage through its tech sector, and sets a precedent for using AI to surveil and control their citizens that is copied by authoritarian regimes the world over—at a time when such nationalist regimes and sentiments are, in fact, on the rise. There is already an “algorithmic social credit scoring system” deployed in the country, using AI-powered surveillance that is used to assign each citizen a social credit score that affects the choices available to them and even their “ability to move around freely”—affecting “who’s allowed to secure a loan, who can travel, and even where their children are allowed to go to school.”

Webb refers to the members of the Big Nine based in the US as the G-MAFIA (Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook, IBM, and Apple), stating:

They do function as a mafia in the purest (but not pejorative) sense: it’s a closed supernetwork of people with similar interests and backgrounds working within one field who have a controlling influence over our futures.

In the US, tech companies “must answer to Wall Street,” but “wield significant power and influence over government.” In China, tech is “beholden to the Chinese government” and the Communist Party.

The imaginative feat of the book is when Webb lays out three potential scenarios that could play out over the next 50 years, ranging from the “optimistic to pragmatic and catastrophic.” She shares visions of a world in which America literally dies, and one in which AI is used to uncover the origins of life itself. To make sure we realize something closer to the latter scenario, she ends the book with prescriptions for a new social contract between big tech, government, and citizens that respects individual liberties and benefits humanity. She lays out a framework and principles to guide a Global Alliance on Intelligence Augmentation, calls for “transforming AI’s business” so that it’s less predicated on surveillance capitalism and surveillance states, and makes a call for more diversity—and more accountability for it—in AI development.

Through it all, even in envisioning the more catastrophic scenarios, Webb remains a believer:

Fundamentally, I believe that AI is a positive force, one that will elevate the next generation of humankind and help us to achieve our most idealistic visions for the future.

The comparison of our current era to the Industrial Revolution has become common, perhaps even cliche, but it is undeniably true. And as with any technology, it is largely a matter of who controls it, and how it is used to control (or at least influence) people. The question is:

What happens to society when we transfer power to a system built by a small group of people that is designed to make decisions for everyone.

One could argue that this is what was done at our nation’s founding, though the system set up them was one of human beings and intelligence making decisions, sometimes disastrously bad ones—ones in which the Americans here before Europeans arrived nearly vanished, and enslaved those the stole from another continent. Can AI be worse than that? Webb’s follow up question about AI is:

What happens when those decisions are biased toward market forces or an ambitious political party.

One could argue that this is already what is happening today, that it has corrupted the system of self-governance set up at our founding. But to ascribe any sense of perfection to that system, or to believe this is the first time it has been corrupted—or that it wasn’t corrupted from the beginning by bias and prejudices—would be naive. It was the work of citizens, and citizen legislators, and activists on all sides pushing to make it better, which it has been at times and can be again. We have a lot of work to do, and we should not be blind to the effects of big tech and AI as we incorporate it into our personal lives or public life. But, in Webb’s view:

The Big Nine aren’t the villains in this story. In fact, they are our best hope for the future.

Webb has a more positive impression of these companies than I do, but I suspect that would be true of most random people I pass on the street. I think the convenience and “frictionless” transactions and relationships to the world around us they offer are more likely to lead to oppression than liberation. But she also knows a lot more about this, having literally written a book on the topic, a book I have had a hard enough time simply reviewing. And, of course, it’s not really an either/or proposition, oppression or human liberation. After all, the living conditions of those laboring in factories in the early industrial revolution were plenty oppressive, and now there is a yearning for a return of manufacturing jobs in the richest nation on Earth. People struggled and fought like hell for conditions to become more tolerable, but in most cases they were still something to be tolerated rather than to aspire to. I know this because I know plenty of people who have worked in factories—my three older brothers and myself included—and some who still do. Part of the struggle to come will be to ensure that AI isn’t a form of surveillance we merely tolerate, or oppressive, but becomes a form of intelligence that can be used in “bettering the human condition.” Because it's not going away.