Rethinking Execution: The 'Salsa Scale' of Embedment

June 12, 2019

"Many organizations run good projects and develop good strategies, with lots of Gant charts, stakeholder engagement and communication plans; they deliver a solid technical output. They probably even have a 'Change Management Plan' that includes briefings and information sharing, but then the Project team is done: The technical solution has been provided, and this output is passed over the fence to Operational Teams. Whatever happens next is not their concern; they have delivered a good 'answer,' even though most Operational Teams never asked the question. Herein lies the problem with execution, and the need to rethink embedment."

"Head office" in most organizations is good at conceptualizing how the world should work and at generating a myriad of frameworks and technological platforms for someone else to work on. Almost all organizations, however, are awful at realizing these conceptual gains on the ground.

"Head office" in most organizations is good at conceptualizing how the world should work and at generating a myriad of frameworks and technological platforms for someone else to work on. Almost all organizations, however, are awful at realizing these conceptual gains on the ground.

In the digital space, emerging research suggests that only 5% of technology projects meet or exceed expectations. This reality is overlaid by the well-worn er. research that broader initiatives have a failure rate of close to 80 percent. Organizations need to rethink Execution.

Jo is the Head of Strategy for a Global Professional Services firm, where she created a superb strategy. The development process had involved almost 300 people across the organization; it had been pressure tested by the Board, and it was ready to fly. Only, it wasn't. Despite the rigour of thought and the quality of outputs, Jo faced a challenge familiar to most people in large organizations: She lacked mechanisms to localize execution. The strategy required different teams, in different parts of the organization, to execute their work in new ways. She was stuck as to how to affect this reality. Of course, she had the old standbys: Leadership team briefings, training, and "information cascades," but she knew none of those would materially shift how local teams worked and the execution of the new strategy.

Many organizations run good projects and develop good strategies, with lots of Gantt charts, stakeholder engagement and communication plans; they deliver a solid technical output. They probably even have a "Change Management Plan" that includes briefings and information sharing, but then the Project team is done. The technical solution has been provided, and this output is passed over the fence to Operational Teams. Whatever happens next is not their concern; they have delivered a good "answer," even though most Operational Teams never asked the question. Herein lies the problem with execution, and the need to rethink embedment.

In their heyday, General Electric undertook a study of such projects—good ones and bad ones. They found something interesting. Like good engineers, GE isolated two variables: the quality of technical output (was the output of the project good?), and cultural acceptance (did people— locally—accept the "thing"?). Repeatedly, they saw a pattern: There were few, if any, "bad" technical outputs. GE created good, thoughtful plans, systems, and processes for people. They rated both variables on a scale of 1 (bad) to 10 (great), and almost all of the technical outputs rated between a 7 and a 9.

However, there was massive variance in the cultural acceptance across these projects. The on. range in there was between 2 and 8; this was the place where new ideas and initiatives died. Failure was a result of poor localization, not a lack of technical ingenuity. When Project Teams were presented with this data, what do you expect that they did? Well, like good engineers, they returned to the "technical output" and tried to figure out how to turn a 7 into an 8. Like their counterparts in most organizations, they assume that a good technical answer is enough. It is not.

“Whatever happens next is not their concern; they have delivered a good “answer,” even though most Operational Teams never asked the question.”

Cultural acceptance is a quizzical concept. To “get” it, you need to recognize that organizations are not the nice neat hierarchical charts and process maps that are drawn up in someone’s desk drawer. Organizations are vibrant, living social systems. At the core of these systems are local tribes. These tribes develop their own mythology, ways of working, and norms; these local drivers are what the cultural acceptance variable tried to capture and better understand at GE. In aggregate, organizations are poor at localizing things (whether strategies or new technology platforms), because they generally lack the language and lens for affecting tribalism. While Project Leaders would tell you that the failure is “leader buy-in,” that is an overly-simplistic explanation. While leaders have a degree of power in organizations, it is not as omnipotent as we frequently characterise. Even Donald Trump has avoided Obstruction of Justice charges in the Mueller investigation because his direct reports ignored him when his commands deviated from cultural and legal norms. This is the reality for most senior leaders, if at a less consequential scale.

Execution is a challenge in every organization, and “embedment” means different things for different technical outputs. Not every initiative and priority needs to be localized in teams across an organization. Unfortunately, organizational approaches to embedment are so shallow and flawed that they are perpetually vexed by the challenges of getting local people to adopt any new ways of working. They resort to the flawed standbys that Jo, the Head of Strategy in the previous story, dismissed as futile.

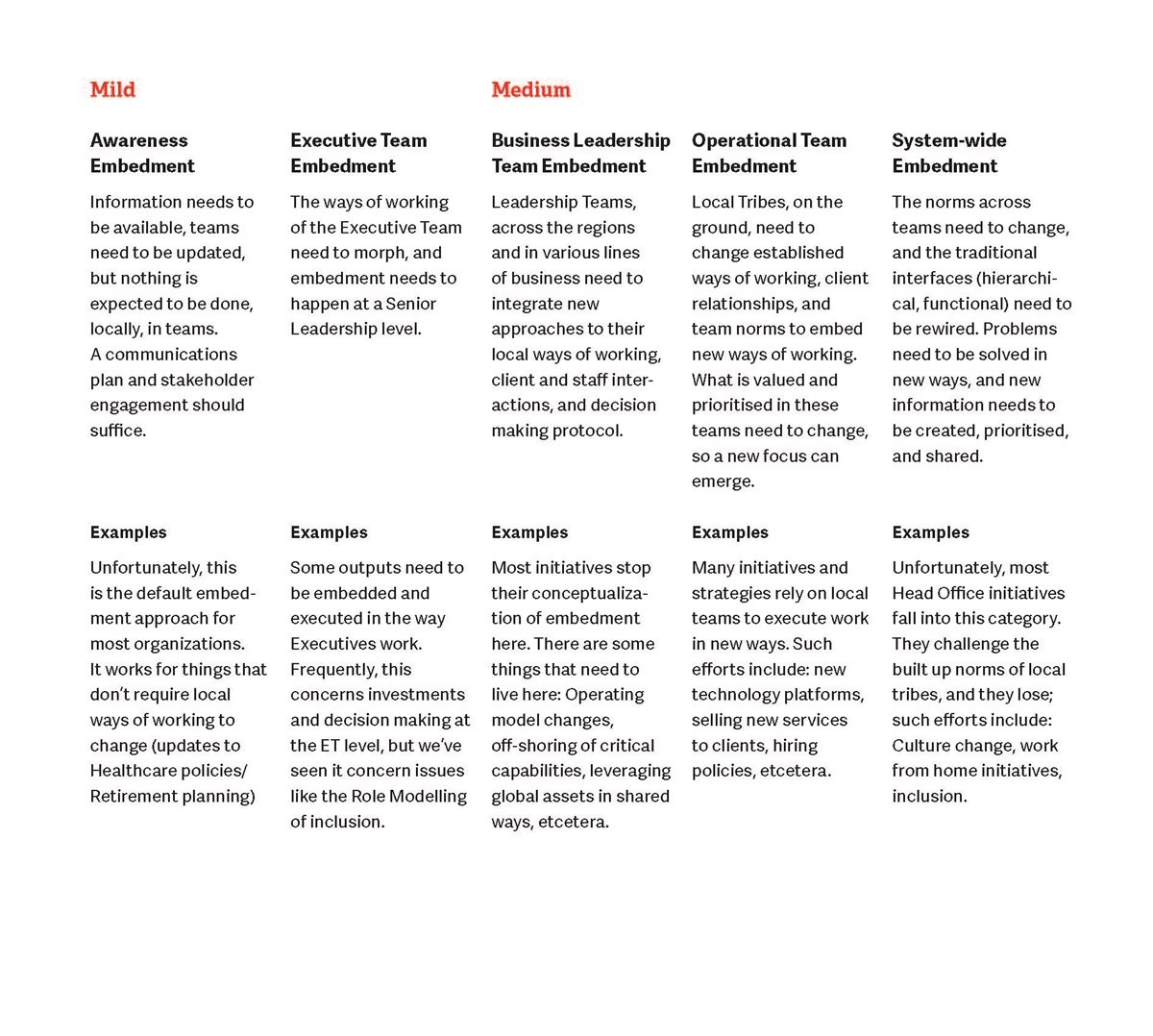

Organizations need a new way to understand these embedment challenges. Based on our work across the globe, we’ve developed the Salsa Scale of Embedment. Like its spicy moniker, the Salsa Scale rates the embedment challenges that organizations face from mild (don’t need a lot of embedment) to hot (embedment and localization is a critical issue that needs to be built into the project from the outset). Organizations need to understand—for any technical output— what degree of embedment is required:

Planning for Embedment

Embedding new ways of working—particularly at the hot end of the scale—is not a sales job that can be accomplished through some on-line training and a good communications pack in the 11th hour. We have found that embedment needs to form a core part of how a project is conceptualized, from the beginning. People frequently tell me that big changes (like culture change) take a decade to accomplish. That is true if you pull the wrong levers. In fact, if you don’t pull the right levers, it’s likely such changes will never really be accomplished. Embedding new ways of working in Operational Teams, or organization-wide, can happen much faster if we plan for embedment. Each technical output needs to be mapped to the salsa scale, and then two things need to be done.

Diagnosing the Status Quo

Organizational tribes thrive by perpetuating the status quo. They have known ways of working that they domesticate new joiners to. They confer status and power, based on their perceptions of “good.” And they create their own stories and mythology. They collude to defend and protect this status quo, and a good embedment plan needs to understand it before they can hope to change it. To embed new ways of working at the hot end of the Salsa Scale, we’ve found a handful of lenses helpful:

- Who has power, locally, in the organization? Influencers and experts don’t show up on anyone’s hierarchical charts, but understanding who they are and where they sit is vital to localizing big changes.

- What gives people status? Organizations confer status in unsanctioned ways. Understanding what gives people status—e.g. “winning work” or “protecting the boss”—helps position embedment plans to actively use local ways of working to their benefit.

- What are the regular gathering places of tribes that we can use to affect this change? All organizational tribes have moments that matter—team meetings, one-on-one meetings, and the like. Understanding what these events are, and how they typically work gives you a way to begin to localize changes before they go live.

- When we’ve been successful at similar changes, what has been in place? Every organization has lessons of successful changes. Study them. In every successful organizational change uses identified levers that are critical to enabling new ways of working.

“Organizational tribes thrive by perpetuating the status quo … and a good embedment plan needs to understand it before they can hope to change it.”

Building Appetite, Not Just Outputs

Once the status quo has been mapped, the most critical enabler of embedment is to use the identified levers to build appetite. Project teams have a nasty habit of becoming obsessed with their technical outputs. They need to view the building of local appetite as more critical to the ultimate success of successful execution.

In one organization we worked with, we identified a handful of “embedment points” that were critical to enabling new ways of working. One of the biggest was client issues—the organization was awful at doing anything new, unless it involved working on a client issue. When people were working on a client issue, they would drop all allegiances and focus on attaining local status by wowing the client. As the organization planned for the embedment of a new technology platform—one that would disrupt ordinary working patterns—the launch was built into and synced with big client problems that people had to come together to solve. As the people came together to solve these very real client problems, they integrated the new technology as a core part of “winning” in that context. The result was that embedment happened as a normal course of work, without anyone ever realizing it.

As strategies and technologies become increasingly disruptive to the ways we normally work, organizations need new and different ways to accelerate embedment. Understanding the status quo and formulating plans to drive localization is critical if organizations are going to execute faster and better into the future.